Brilliant Bogs I: A Brief History of UK Peatlands; climate, land-use and erosion

In my last blog post on the importance of upland wet heath, I briefly talked about the importance of peat both in terms of Carbon and hydrology, so in this first part, I want to provide a historical overview to our UK peatlands, their formation, degradation and gradual restoration, before going into more detail on their ecology in a second post. This post will provide an introduction to a peatland bikepacking project I am undertaking in July, partly funded by the John Muir Trust.

A Primer on Peatland Terminology

Whilst I try to explain everything in plain English on my blogs, it is unavoidable to delve into scientific terminology. As with all my blogs, I try to explain all terminology as fully as possible (and highlight in bold) and for this post, it is helpful to open with a section on the most commonly used terms that will be used within this blog.

Large expanses of blanket mire seen in the Flow County have formed through a natural process of climatic change after the termination of the last glaciation 10,000 year before present. Peatlands are typically vast environmental systems, they are also ancient landscapes principally forming as we moved from a post-glacial cold/dry climate to a interglacial Atlantic driven, wet and humid climate causing a change from a environment where evapotranspiration (loss of water from the plant surface) exceeded precipitation to a system where precipitation exceeded evapotranspiration. From a soil perspective, this leads to a decease in litter decomposition rates, leading to over-saturated soils that slowly become more anoxic (lower oxygen levels) for the roots of trees. A gradual process of arboreal trees dying out, due to low oxygen and an inability to sequester enough nutrients from the soil, coupled with the colonisation of dead wood by mosses, lichens and liverworts begins the very slow process we call ombrotrophic mire development. This process differs between blanket systems and lowland valley systems, but the foundations are the same with a gradual slow build up of partially decomposed organic matter, that is compressed by the weight above, which gives us the black stuff called peat. It is at this point I want to add in a caveat from the paleoecological record; as its an important one and often misrepresented by environmental correspondents such as Guardian journalist George Monbiot, and that is the misconception areas like the NW and North Highlands of Scotland should still be (and restored back to) a forest as it was early Mesolithic farmers clearing the forests that initiated the onset of mire development. As someone with a PhD partly in palaeoecology, I have not read one paper that has been able to conclusively say that the mesolithic populations in Scotland were the principal cause of mire development, and in contrast a paper in 2007 by palaeoecologist Roger Tipping showed the reverse that mire development was already well established in North Scotland by as early as 8000 years before present. We know that farming settlement didn’t happen here until the later Neolithic period some 3000 years later and evidence also indicates farming communities trying to push back the encroaching peatland for cultivation. In the more central and southern parts of Scotland, where blanket bog is only found in higher altitudes, it is also likely that the only human activity would have been from hunter-gathering activity or transhumanist pastoralists moving their cattle between summer and winter pasture grounds. Coupled with the present day importance of these ecosystems, as carbon stores and areas of sequestration, as botanically unique landscapes containing important numbers of bird species and the call of the RSPB that the focus in Northern Scotland should be peatland restoration not tree planting, it is time to put such myths about the anthropogenic initiation of bog growth to sleep before damage is done.

Peat Matters: A primer from the previous blog

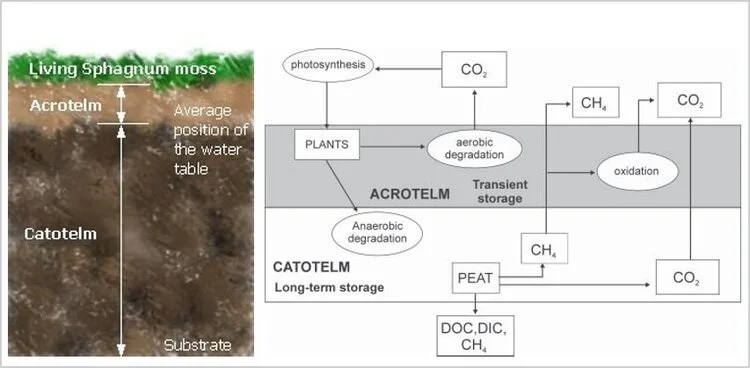

Globally, Blanket bogs and valley/basin bogs are incredibly important for carbon sequestration, especially those that retain their diverse peat building sphagnum communities, this also makes them major carbon sources as peat depths can extend to 10m below the surface. The peat mass (Figure 1) when healthy is hydrophillic and contains a lower permanently wet lower layer (Catotelm) and a seasonally dry upper layer (Acrotelm) which is typically only about 10 cm deep. Keeping the peat mass healthy is the surface vegetation layer on top (I like to think of it as the sun tan lotion that stops you from burning), once this surface layer is removed it exposes the seasonally wet/dry upper layer, not an issue during wet seasons as it will remain hydrophilic but once in the dry season the peat starts to desiccate becoming hydrophobic and easily erodible, which is what occurs once the rain comes back and starts to transport it away.

Figure 1. Hydrological structure the peat mass and the exchange of carbon

Peat formation is a one-way process. The material only remains as peat if the ground stays saturated so that air is excluded. If the peat becomes drier the process of decay will occur and it will be lost either as plant food, as wind blown particulate matter or acidic-humic water soluble compounds in the water system. This is why the maintenance of healthy peatlands is incredibly important in the battle of climate change, because dry degraded peatlands represent a major loss of carbon both directly to the atmosphere through peat oxidation, through particulate carbon in the wind and water and soluble carbon (mostly humic acids) in the water course. Degraded peatlands are also difficult to re-wet, reinforcing the drying cycle, so peat only accumulates reliably in places that are permanently wet, either because of a cool, cloudy and high precipitation climate or a permeant groundwater table in rock basins; most of the good peatlands in Northern Scotland have both. Due to the proximity of the Atlantic Ocean to north-western and northern Scotland means there is generally peat formation over most of the land in west Sutherland, but in the east oceanicity is insufficient to maintain peat growth where the peatland has been drained on estates and afforested areas, however it still grows well in areas with a ground basin. This East-West difference is is also marked by the different flora due to the permanently damp, but not wet and slowly decaying peat.

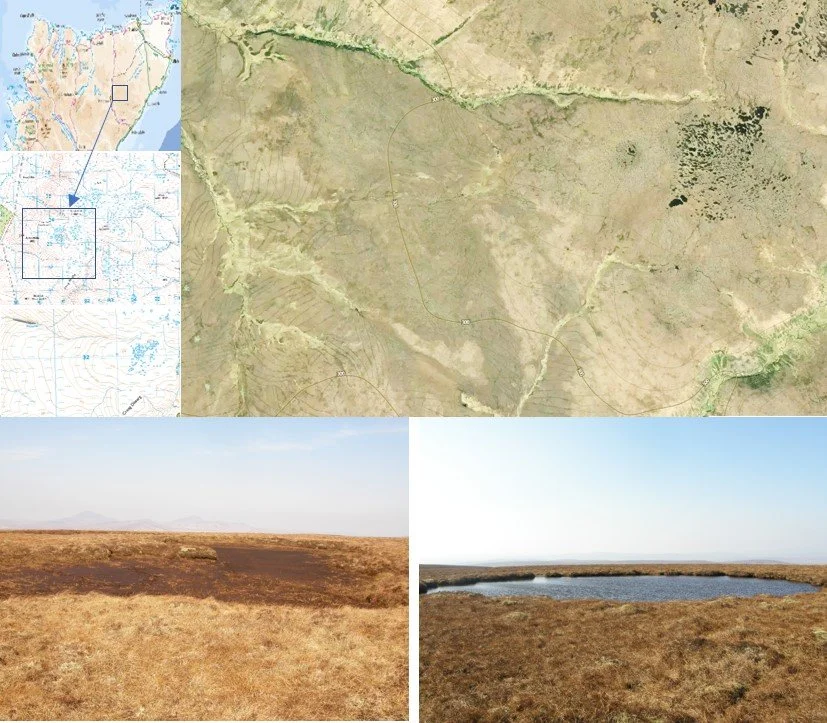

Figure 2. A typical watershed plateau bog pool system, located in part of the Flow Country, Caithness. Theses bog pool systems are incredibly complex with a mixture of permanent larger pools and seasonal pool. Fringing and surrounding them is a complex microtopographic vegetation gradient determined by water table differences of a few centimetres.

In these mostly intact blanket mires of the Northern Highlands, on large watershed plateaus you find mire pool patterns with a mix of permanent and seasonal bog pools, they are magical places to be (Figure 2) and contain a complex wet-dry microtopographic vegetation gradient with a keystone species of Sphagnum spp (covered fully in the next post), however in some areas you find through deer trampling (figure 3) and burning that the vegetation bridge that has separated the smaller pools has now disintegrated, this exposes the peat underneath which subsequently starts to erode allowing the smaller pools to coalesce into a bigger one.

Figure 3: Red Deer on peatland

As this has repeatedly happened during dry periods the pools have become dried out creating permanent peat hollows, the fringing wet sphagnum communities are replaced with drier communities leading to a landscape that is prone to damage by fire and a starting point for the blanket erosion discussed next. Historically our management of peatlands in the UK has lead to continued drying out; in the 1960s there was a campaign to dry bogs by ditch draining to expand marginal agriculture; here on Orkney is is estimated that there has been a 50% reduction in the islands peatland through reclamation; in the 1970s areas including the Flow Country in Caithness were drained for afforestation schemes, with many well known celebrities buying into it. Thankfully our mindset has largely changed; and we know actively restore degraded sites, atmospheric pollution has largely decreased, however out land management is still largely unchanged in many areas and continues to be of concern.

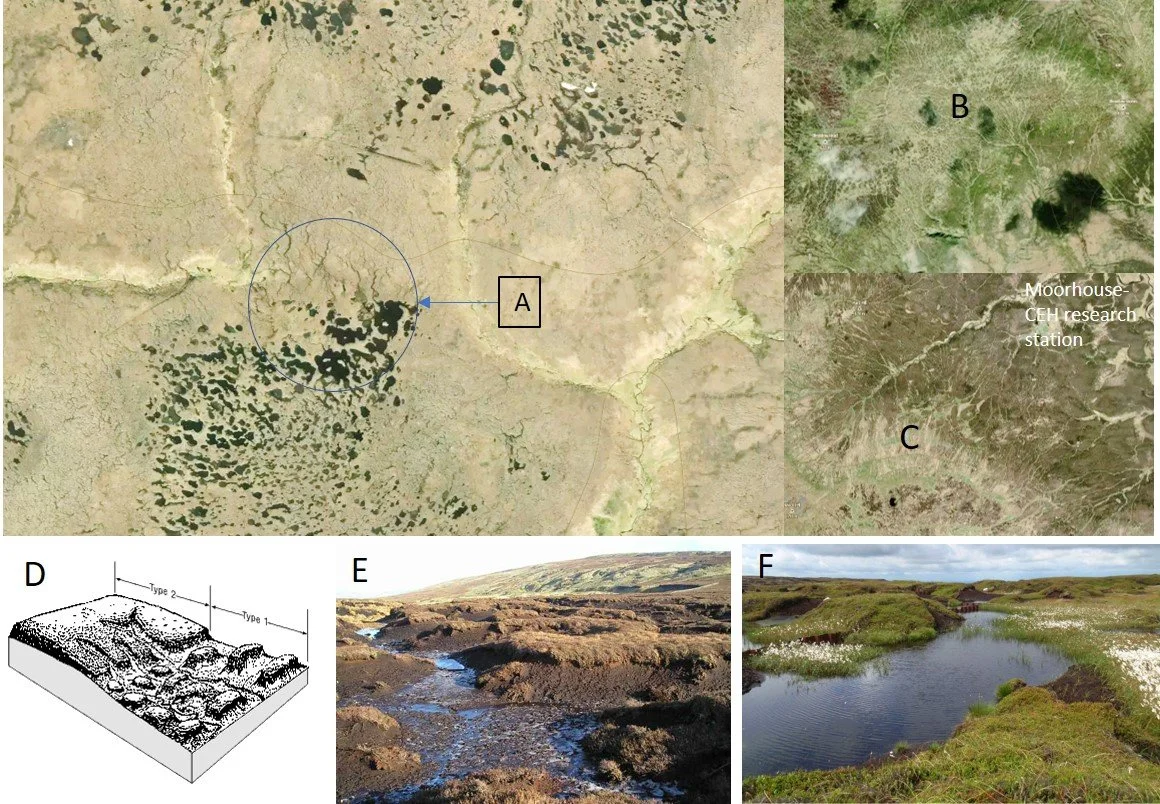

Figure 4. Patterns of erosion, individual figures explained in main text

It is incredibly important to try to restore all degraded peatlands to some form of peat-based vegetation community, in the past I have been asked why not re-wood areas in South Pennines instead of keep them as peatland. The answer comes back to the carbon budget and climate change, the purpose of peatland restoration in the Peak District is to prevent further carbon loss, and the best way to do this is to re-establish a blanket of vegetation on what peat remains. Planting trees dries the peat even more, lowering the water table further and adds to the loss of carbon from the system, the trees that are planted as saplings will do little to balance that negative loss out. In the North Pennines, Central and North Highlands of Scotland (including all the islands), and peatlands of North Wales restoration is also about restabilising a healthy sphagnum community, which can slowly establish a microvegetation-topographic gradient and restart the peat building and carbon sequestration process, as well as prevent loss of carbon from the peat mass.

UK Peatland degradation, the process of erosion and recovery

The process of peat erosion led to the extensive patterns that dominate the South Pennines, and once the North Pennines (which has largely recovered) are complex and what we now understand has been driven by several external (climate and sulphur dioxide air pollution) and intrinsic (predominantly burning and grazing) factors that have combined to form a ‘perfect storm’ over 1000-2000 years. What we don’t know is exactly what the pre-erosion peat mass of Kinder Scout and Bleaklow looked like, as the erosion there is historic and pre-dates all available photography, however its topographic situation; that of a flat area of peat with steep-sided drainage fringing it, does resemble the topographic situation of the watershed mire bog pool communities of Northern Scotland (Figures 2 and 4A). Unlike most of the Flow Country of Northern Scotland, these pool communities sit at a higher altitude to the surrounding landscape, and their hydrology and hydrochemistry are predominantly controlled by the atmosphere, so any shift in atmospheric chemistry due to pollution will adversely affect them, in addition any alteration to the peat surface, through removal of vegetation, alterations to water table, and small areas of degradation will have a greater impact than on the larger, low-lying areas of peat below as inputs of water into these plateau areas if not retained, will be lost into the watershed drainage systems.

Through my time working on the restoration of eroded peat in the South Pennines, I became familiar with the two main categories of erosion first described and named after Bower (1960, Figure 4D) as Bower Type 1 dissection erosion on gradients of less than 5 degrees (highlighted in figure 4C from Bleaklow, South Pennines and photo, figure 4E), which results in a landscape of isolated ‘peat hags’ amongst a sea of mineral and thin peat, and Bower Type 2 linear gully erosion on slopes of 5 degrees or greater, which we find on sloping gradients that drain towards drainage channels (Figure 4C shows these gullies at Moorhouse NNR in the North Pennines, which have all naturally revegetated). We know that many of the type 2 gullies start off as either, headward erosion from the peat margins, peat runnels created by the removal of keystone vegetation species or seepage on weak lines, this latter one is often connected to changes in sub peat (catotelm) hydrology and the formation of peat pipes, when combined with removal and degradation of the peat surface above them, this can lead to rapid creation of a gully, that is deepened and widened with further headward erosion.. In addition, we know that fire can be a major component in the creation of the extensive type 1 dissection erosion seen on the flatter areas.

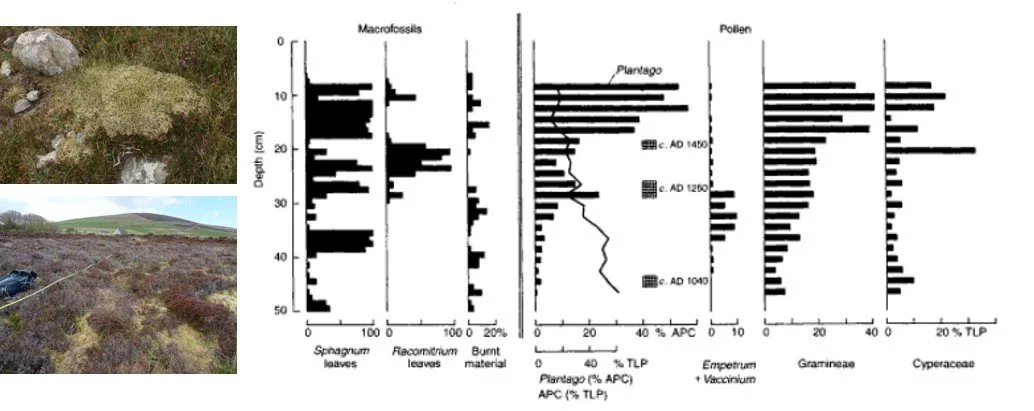

Although we don’t have photographic evidence or extensive spatial botanical data to what Kinder Scout and Bleaklow plateau was pre-erosion, we do thanks to the work of palaeoecologist John Tallis have an understanding of the broad vegetation changes that have occurred throughout the last 3000 years. Tallis wrote several papers in the Journal of Ecology throughout the 1980s and 1990s, attempting to understand the historical context to the erosion, in his Tallis (1994) paper he described the pool and hummock patterning (a climatically controlled microtopographic vegetation gradient in ombrotrophic peatlands, discussed in detail in the next post) which is central to the peat formation process. From his peat cores, he concluded that this slow dynamic process; where over many cycles of climatic changes sees pools expanding in wetter periods, or hummocks upgrowing in drier periods, had slowed in the South Pennines during and then following the Early Medieval Warm Period (an abrupt period of much warmer climate c. AD950-1250). The result was a gradual process of the hollows drying out and creating an avenue for erosion and the onset of Type 1 dissection erosion. Initially, Tallis (1994) suggested this as early as AD900-1000 but later revised this to c. AD1450 (Tallis, 1995) after analysis of the Racomitrium lanuginosum layers, which autoecology puts it as an oceanic species indicated a shift to a wetter, humid climate, which could be seen after these dates in the stratigraphy (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Frequency histograms of macrofossils from Tallis (1995) paper, for an intact bog site in North Wales, which he used to revise the initial date for the onset of peatland degradation in the South Pennine peats. The presence of R. langinuosum leaves followed by Sphagna suggesting the climate had shifted back to a wetter climate to allow the continued growth of the peatland. The lack of both species in the South Pennine cores at the same stage he attributed to the degradation of the peat mass, resulting in a loss of macrofossils due to exposure to oxidation.

Figure 6. A blocked drain on the RSPB Forsinard Flows Reserve, showing over 75% infilling with Sphagnum.

This early but slow first phase of climatically driven peatland degradation was then accelerated in the period we call the first Industrial Revolution (AD1700 onwards, Tallis, 1985). The industrial revolution is easily marked in the palaeoecological record both in peat and lake core records, for its decline in those species sensitive to high levels of sulphur and nitrogen oxides, for the South Pennines it is notably marked in the loss of R. lanuginosum from the peat record. In addition, the high levels of nitrogen being deposited along with increased management for grazing and shooting, led to an increase in the number of grasses plus an increase in density of C. vulgaris (Bell Heather) which was allowed to establish as thick, metre high bushes. By the time Nitrogen and Sulphur levels had decreased in the South Pennines the vegetation communities had changed beyond recognition, and the erosion features that we now associate with the landscape were well-established and can be seen in the earliest aerial photography from the 1940s. The story doesn’t end there, however; if we move to the North Pennines AONB (Figure 4C) which to a lesser extent became eroded, but through a combination of less marginal climate and pollution levels dropping quicker, along with careful management we see that many of these areas of Type 1 and Type 2 erosion have stabilised and slowly revegetated, frequently starting with another key species of blanket bog, Eriophorum angustifolium (Common Cottongrass), which acts to both stabilise the peat surface and create a microhabitat that allows Sphagnum and other bog species to colonise at a slower growth rate. We also see this in the South Pennines, where blocks of peat have fallen into the gully, damming it and allowing peat to build up behind, they then follow the same colonisation process as in the North Pennines. It is this natural process that we replicate in peatland restoration, damming gullies and drains to raise the water table, allowing peat runoff to build up and species to recolonise. It is a simple, but highly successful technique and it works because it is replicating a natural process, it will take decades to see whether what follows restarts the process of hummock growth and pool formation, and this will largely be down to the local species pool and the local climate, however, the results from large scale restoration in the Border Mires, Northumberland and RSPB Forsinard Flows Reserve, Caithness are very encouraging and back up the opinion of the RSPB that the focus should be on peatland restoration appose to tree planting.

References

Bower, M.M. (1960) Peat erosion in the Pennines. Adv. in Science, 64, 323-331

RSPB (2020) Transformational peatland strategy needed to tackle Scotland’s nature and climate crisis.

Tallis, J.H (1994) Pool and hummock patterning in a South Pennine peatland mire 2: The formation and erosion of the pool system. Journal of Ecology, 82: 789-803

Tallis, J.H (1995) Climate and erosion signals in British Blanket Peat: The significance of Racomitrium lanuginosum remains. Journal of Ecology, 83 (6): 1021-1030

Tipping, R. (2008) Blanket Peat in the Scottish Highlands: Timing, cause, spread and the myth of environmental determinism. Biodiversity and Conservation, 17: 2097-2113