Brilliant Bogs II: Patterns within Patterns - the microtopographic world of blanket bog vegetation

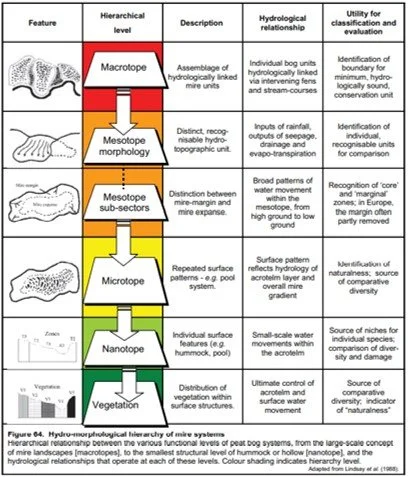

Figure 1. Lindsay et al (1988) hydromorphological hierarchal framework for describing mire systems

Welcome to Part 2 of my blog series on Brilliant Blogs, having dealt with the physical fundamentals of peatlands in Part 1, in this blog I want to focus on the hydroecology of these landscapes. In a previous post on upland heath and bog, I broadly talked about some of the National Vegetation Communities (NVC) we find in these landscapes but these NVC communities poorly reflect the variation and diversity found across them. Blanket Mire vegetation communities are poorly defined in the NVC; the NCV defines only eight major ombrotrophic bog communities, including three bog pool and one mire margin, within the 38 ‘mire’ communities in Britain (Rodwell, 1991), The remaining 31 are fen communities, and hence fen communities are frequently well described in terms of their vegetation classification. During the 1980s increasing importance was placed on vegetation types within the smaller-scale microtopography, however much of this was based on raised bogs (Lindsay et al., 1988), the CORINE classification was an example of dividing vegetation between bog hummocks, ridges and lawns, bog hollows and bog pools. However, it was Richard Lindsay, in 1988 who designed a classification based on microform vegetation types based on a collection of 25000 samples from 65 British sites. It is his classification that will form the centre of this blog, as a walkthrough of the hierarchy of landforms that can be found and the species within them. In the hierarchal system that we describe blanket mire systems, it is easiest to start at the largest landscape level and work down, Lindsay et al (1988) came up with a six-level system which can be seen in Figure 1 and begins with the macrotope which can be seen as all the components of a mire system that are found within a single drainage or watershed system and is often only fully appreciated and delimitated by looking at maps and aerial photography, for where the peat mass ends and the mineral soil, drainage system etc begins.

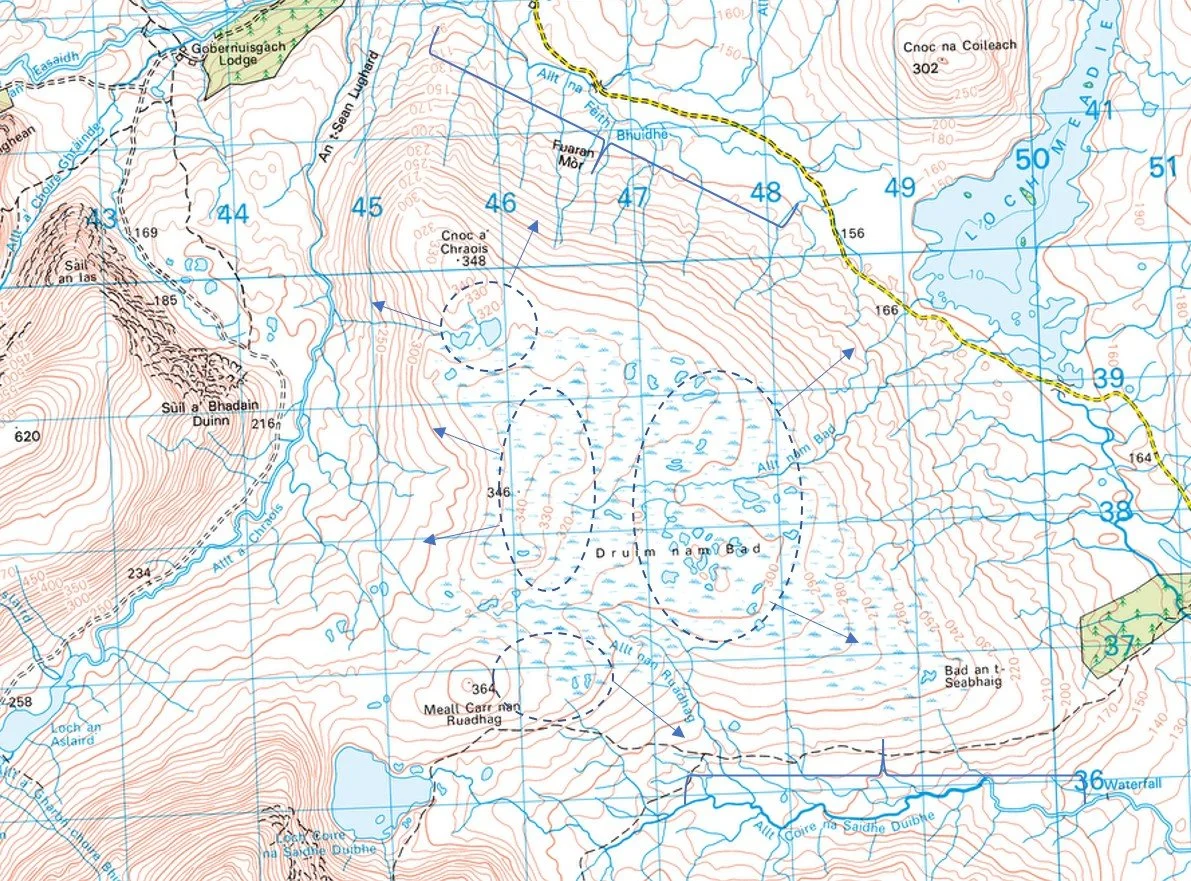

Within Northern Scotland (Figure 2), the macrotope level can encompass tens of kilometres as in the Flow Country, Caithness or within 1-2 kilometres in the far North-west where development is constrained by lochs, lochans, mountains and drainage networks. On the left of Figure 2 the Druim nam Bad system, sits on a large watershed plateau, it has two main spurs and three valleys that drain directly down from the mire itself to the east. In contrast within the expanse of the far North-west highlands, the macrotope is likely to be on a small area of plateau, a flat valley bottom or a concave area linking some lochans and would require being on the ground at the site to delimitate them. Understanding the potential for individual mire units within this large landscape is important as it takes us down to the next level the mesotope

Figure 2. Examples of blanket mires at the macrotopes levels; on the left a large expanse of higher altitude blanket bog of approx. 31km2 and delimitated clearly by three main drainage networks that feed into the surrounding lochs; in contrast in the far North-west as talked about here, on the right macrotopes can be no more than 1-2 kilometres in size being confined by the high mineral sided mountains, deep lochans and dense drainage pattern. Aerial photography has been colour corrected to allow for clear identification of features. Grid squares represent 1km in the OS maps.

The mesotope unit is often sufficiently recognisable to be given a name, however in Northern Scotland, this can often be sporadic as the name on an OS map can be printed across several mesotopes, in addition in the far north-west the confined nature of the landscape, often means the macrotope is also the single mesotope as in a single area of watershed mire or spur mire sitting on a flat concave area of the lower part of the mountainside (Figure 2, right-hand side shows two examples of this for the Glen Canisp and Assynt area. The Druim nam Bad system in Figure 2 (left-handside) is an SSSI and the entire macrotope covers 31km2, within the macrotope SNH identifies the mesotopes of a central watershed mire system, that sits at c. 300m asl, its also recognises both valley mires and raised mire mesotopes lower in the macrotope. We can identify these mesotopes by working out the hydrological flow lines for the mire, which are linked to the overall morphology of the system (Figure 3) we can also start to define the mesotope sub-sectors or where water will flow from higher to lower ground.

Figure 3. Enlargement of the Druim nam Bad macrotope, and identification of possible mesotopes and the hydrological flow lines from each unit. It would require a site visit to confirm the information, but using contours and features on a map we can identify areas of potential interest to focus a field visit

Having now defined the larger hydromorphological units, we can move into a closer study of each one and begin to identify repeating features within it, these features may be pools of varying sizes, and more commonly there is the classic patterning of hummocks and hollows formed from he complex assemblages of Sphagnum spp. that define the microtopes within the mesotope. These patterns create a fingerprint across the bog and can be easily identified from aerial photography, and they are an essential part of understanding the mire surface and the smaller-scale vegetation patterns with-in. We have now abandoned the popular concept of hummock-hollow growth, which basically suggested that hummocks grew until they collapsed and started to form a hollow, and hollows then grew up in hummocks and adapted Barbers (1981) ‘climate phase model’ for growth instead which to put simply states that in wetter, high oceanicity climates the ‘hollows’ will expand out and compress the hummocks and vice versa in a dry climate. This model plays out well across the UK as well, where we see a high frequency of patterned pool mires in the north-west and far north of Scotland, where annual rainfall exceeds 2500mm/year but more hummock-featured bogs across the eastern parts than crossing the border into England (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Lindsay et al., (1988) figure showing the relationship between microtope pattern and climate, with the North of Scotland (Example from Caithness flow country in top right), displaying a higher frequency of larger pools and ‘wet’ vegetation that can be maintained due to the high oceancity in the region. Within these microtopes, slope determines both the size and spacing of the pool, in the grey-scale aerial image in the lower right, we see a) larger pools in the centre of the watershed mire, these pools become b) smaller with larger area of less-wet vegetation on the watershed margins, c) finally where the mire slopes down on a gradient of >5 degrees we find no pools and a gradient of dry and less dry vegetation, typical of wet heath.

Along with climate, slope angle (Figure 4, bottom right) plays a large part in determining the frequency and size of any pools in the microtope; in regions like the Flow Country in Caithness, the overall slope gradient is a very low concave or convex area, this means that the water table can be maintained across the surface with only narrow peat ridges needed to separate out the individual pools. Where the gradient is steeper, for example towards the edge of a watershed mesotope or in the complex landscape of the north-west of Scotland, pools will be confined to the flatter sections, with denser drier ridges on the slope, when we reach 1 in 5 gradients as on the slopes of the watershed mire, the pool element can no longer be maintained and a typical wet health community establishes of dry and less dry vegetation patches. It is this later community that has unfortunately often been subject to drainage on estates and forced into a dry monotonous Calluna monospace.

From the overall microtope surface pattern created by the vegetation, we move down to the vegetation units themselves. the nanotopes, vegetation communities controlled by the small-scale water movements within the acrotelm (the upper layer of the peat see Brilliant Bogs Part I). The nanotope is an incredibly useful unit for understanding the ecology as it’s where we find species being replaced/displaced and can begin to understand the impacts of degradation and erosion on the mire surface. Until the work by Lindsay, Riggall and Burd (1985) we only had the vague terms ‘hummock and hollow’ to describe these vegetation units, they were slightly expanded on to include lawn (a terrestrial zone lying above the water table) and the sphagnum carpet, a zone of aquatic sphagnum species (the places people often step onto thinking its solid ground, and end up with a wet walking boot or two).

The term ‘hummock-hollow’ is still over-used in describing peatlands today and unfortunately still has attached to it the idea that hummocks grow, then collapse to become hollows, a largely abandoned model and replaced by Barbers (1981) climate phase model. Even expanded to include the words, lawn and carpet, doesn’t even begin to describe and explain the complexity of communities that exist in blanket mires (see images above); to illustrate a few includes a pool surrounded by floating S, cuspidatum (top left), a drain being overgrown by the linear species E. angustifolium (middle top), complex tussock of green and red sphagna (bottom left) and varying lawns and micro-hummocks amongst an abandoned peat cutting here on Orkney (bottom middle). To present a more cohesive form of vegetation community identification, Lindsay, Riggall and Burd (1985) suggested a series of interlinked features, those relating to undamaged bogs are summarised in Figure 5, but they also included a series of types relating to the damaged blanket mires of the UK, both in terms of erosion, fire damage and draining. These were subsequently developed further with the then Nature Conservancy Council (NCC) in 1989 and the Joint Nature Conservancy Council (JNCC) in 1994

Figure 5. Distribution of the nanotopes suggested by Lindsay, Riggall and Burd (1985) not included here but described further in the text are the erosion nanotyes which are of particular importance in UK peatlands.

As this is a blog, as opposed to a textbook or journal article, instead of simply listing the nanotypes I will go through a series of pictures from blanket mires and talk through the features. There are 13 nanotype units, with 5 relating to eroding or damaged bogs (which I talked about in Brilliant Bogs Part I). The remaining eight can be found on both undamaged and damaged bogs, and certain ones are almost entirely restricted to the undamaged, intact and high oceancity mires of the west and north of Scotland. We start with the highest and most densely vegetated features the hummock, which is broken into 3 units; T1 (T= Terrestrial) low ridge (just above the water-level and often referred to as a sphagnum lawn), T2 high ridge (c. 15-25 cm above the water table) and often the prominent nanotype of a blanket mire the T3 Tussock (>25cm above the water table) found frequently on mire margins or eroding mires, Tallis (1995) in his paper on the importance of R. lanuginosum posed several (still unanswered) questions on the significance of this moss on the tops of T3 Tussocks, relating to repeated burning and termination of peat growth.

The images above show nicely the variation in the first three nanotype units, starting with the left and the T1 low ridge which sits just above the water surface and is marked by the presence of more than just Sphagnum, moving to image 2 from my NPMS on Orkney we find T2 high ridges between the denser T3 tussocks of Calluna vulagris and Vaccinium myrtillus. The T2 low ridges here also contain sedges and butterworts. Third in the series, we have the R. lanuginosum topped T3 hummocks that also here interlink with other units relating to a damaged mire surface. Finally taking a broader view, in the image from the Border mires we see all 3 unites interlinking to produce the beautiful red-topped Sphagnum hummock. Both the T1 and T2 units, being a mix of wet and dry habitat can provide a microworld of diversity for vascular species (below images), and perhaps show why the moss has been so well covered by horticulturists (much to the demise of lowland raised bogs).

Alongside the 3 intact mire surface units, there are 2 associated with damaged/eroding mires; T4 erosion haggs (see image below - which form part of the distinct landscape of both Kinder Scout and Bleaklow in the Peak District) and T5 peat mounds, a somewhat odd feature confined to the NW of Scotland that no-one knows how they originate.

From the terrestrial (T) features we move to the aquatic (A) features, those where the water table is at or just above the surface; A1 Sphagnum hollows, A2 mud bottom hollows, A3 drought-sensitive pools and A4 permanent pools. Beginning with A1 Sphagnum hollows which sit below the T1 feature and comprise a thick mat of aquatic S. cuspidatum (Figure 7), often giving the false impression of solid ground, until someone steps on it and sinks to their thighs. Aside from almost one species of moss, this feature is fairly low diversity with most other bog species being confined to the margins around it.

Figure 7. Left: Don’t be fooled by the solid appearance of the A1 Sphagnum hollow filled with S. cuspidatum, it is nothing more than a floating raft of moss, Right: Watch out for mini aliens about - Drosera intermedia (Oblong-leaved Sundew) a carnivorous plant that occupies the A2 mud hollows

A2 mud hollows occur in shallow pools of no more than 20cm and are solid enough to stand on, consisting of either bare peat bottom (the ‘mud-hollow’) or a mat of semi-decomposed Molina caerula (Purple Moor Grass) and is often associated with the alien-like cherry red species of Drosera intermedia (Oblong-leaved Sundew - Figure 8). This unit is generally confined to the north-west of Scotland, where the topography allows for small isolated hollows to develop.

Figure 8. A3 and A4 pool complex panorama from an area of watershed mire on Knockfin Heights, Caithness. The surrounding vegetation is a mixture of the terrestrial vegetation units described earlier in the post. A3 drought-sensitive pools occupy the outer edges, where the peat mass curves and the pool is shallower. A4 permanent pools occupy the centre of the peat mass, where the depth is deeper.

We then move on to the first of two pools, that frequently form a major part of watershed mire mesotypes. A3 drought-sensitive pools and as the name suggests, these can dry out in a prolonged dry climate and are therefore susceptible to degradation if the occupying land is burnt, grazed or over-trampled. They commonly sit 20-40cm above the water table and may be a mix of open water and floating mats of Sphagnum, aside from moss they tend to only support Menyanthes trifoliata (Bogbean) or Eriophorum angustifoilm (Common Cottongrass). It is interesting as many revegetated gullies show the same species whether naturally revegetated or ditch-blocked, which suggests this is a natural pathway back to an active bog environment post-erosion.

Figure 9. Left to Right: A3 drought sensitive pool (Knockfin Heights) this pool also on inspection shows signs of peat pipe formation at the base, an indication of prolonged drought and a precursor for erosion; A4 permanent pool (Knockin Heights) from the same complex as A3 pool, however is deeper and maintained; A4 permanent pool (Knock an Alaskie) with Bogbean.

Finally, we arrive at A4 permeant pools, the characteristic mire feature that gives the flow country its name and is found (and now mostly restricted) to the north and west of Scotland. These pools may be 3-4m deep, extending in parts to the mineral basal sediments and surrounded by solid vertical walls. Vegetation is extremely limited due to the depth and temperature but can support floating M. trifoliata and mats of S. cuspidatum and be home to several aquatic invertebrate species. The individual ‘vegetation’ bridges separating the pools are often no more than 50cm across and in dense deer forests (estates) can become degraded leading to pools coalescing and no longer being hydrologically stable (see images below showing a range of permeant pools, including one that has dried out and is being colonised by surrounding vegetation).

It’s with the necessity that this post finishes with four features found on degraded and eroding mire surfaces (although not all negative), as described in Part 1 , the blanket mires of the UK have been subject to almost continuous disturbance from the human population, either reclaimed for agriculture, drained for forestry, along with burning for grouse shooting, on-top of long-term changes caused by historic climate change and historic pollution. Lindsay, Riggall and Burd (1985) split them into 3 features E1 (for erosion) regenerating erosion gullies, E2 active erosion gullies, Em1/2 micro-erosion and a final Tk tussock unit which takes into account the often dense tussock structures found on repeatedly burnt mires and those that have recovered. The photo sequence below shows how the sequence can interplay, the top three photos show the negative cycle of erosion from micro-erosion to active erosion gullies (and the presence of T4 peat hags) and the bottom three the positive cycle of revegetation of the three erosion phases. The extent and composition of E1 or Em1 types are dependent on the local hydrology and species diversity of a mire surface.

Figure 10. Examples of erosion features found on blanket mores, left to right: An example of Tk tussock unit commonly found bordering active Em1/2 micro-erosion features, An E1 regenerating erosion gully infilled with a dense carpet of Sphagnum spp.; E2 active erosion gully and a E1 regenerating gully with pioneer Eriophorum angustifolium (Common cottongrass)

E1 regenerating erosion gullies was the focus of my PhD thesis (Crowe, 2007), it is believed that 50% of all previously actively eroding gullies are now regenerating; as previously mentioned many revegetate to a pseudo-A3 temporary pool vegetation community with E. angustifolium and if present on the mire surface Sphagnum. Over a decadal period of stability, they then move into the terrestrial communities, composed of the local species on the mire surface, which creates a further dam in the gully allowing the process to repeat upstream. Of course,e if only 50% are regenerating, then 50% are still E2 active erosion gullies, these gullies include the Bower Type 1 dendritic patterns in the South Pennines, which require a lot of human intervention to enable any revegetation. They have cut down fully to the basal sediments and sinuously wander amongst the T4 peat hags described earlier, alternatively, they may be newly formed gullies formed out of catotelm sub-peat pipes. The formation of these peat pipes is somewhat a mystery but their collapse leads to a smooth preformed half-pipe structure, that can quickly be widened and deepened with time. If these peat pipes are simply a facet of an old mire system, then the management of the mire surface becomes increasingly important not to cause damage to the vegetation layer above. Where E2 gullies aren’t formed by peat pipes, they are linked to the Em1/2 micro-erosion (1 - showing signs of revegetation, 2 - actively eroding). I discussed the various mechanisms and triggers that lead to this type of erosion in the Brilliant Bogs Part I post, but the presence of this feature (and it is found in almost all mire macrotopes) is often through burning or excessive trampling of scooping hooves, and is a warning to stop; and allow the mire surface to recover, which can be quick if it remains as just surface micro-erosion. Where we often find the Em1 micro-erosion, we also find the final unit Ts Tussock, these tussocks are often in the form of dense clumps of E. vaginatum (Hares-tail Cotton grass), and other species can include Trichophorum cespitosum (Deer Grass - Figure 10) and R. lanuginosum topped T3 tussocks which Tallis (1995) potentially linked to repeated burning on the Peak District Mires and were often visible on the edges of erosion gullies.

So hopefully this post has given a good overview of the landscape and the general vegetation patterns within it of Blanket mire peatlands. I have kept it general in this post, as I plan more detailed posts with respect to certain features, plant communities and species as my surveying and bike-packing project develops this year. All future posts will appear on the main page as featured posts.

Thank you for reading

References

Crowe, S.K. (2007) The natural re-vegetation of eroded blanket peat: Implications for blanket bog restoration. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Manchester

Barber, K.E. (1981) Peat Stratigraphy and Climate Change: A palaeoecological test of the theory of cyclic peat bog regeneration. Rotterdam

Lindsay, R.A., Riggall, J. and Burd, F. (1985) The use of small-scale surface patterns in the classification of British Peat. Aquilo Seria Botanica, 21: 69-79

Lindsay, R.A., Charman, D.J., Everingham, M.F., O’Reilly, R.M., Palmer, M.A., Rowell, T.A. and Stroud, D.A. (1988) The Flow Country: The peatlands of Caithness and Sutherland. JNCC

Rodwell, J.S. (1991) British Plant Communities, volume 2: Mires and Heaths. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Tallis, J.H. (1995) Climate and erosion signals in British blanket peats: The significance of the Racomitrium lanuginosum remains. Journal of Ecology, 83 (6): 1021-1030